Brown offers transformational opportunities for students to conduct summer research with faculty colleagues and present results at the Summer Research Symposium.

Designing tomorrow’s lunar missions: Brown’s rising junior WaTae Mickey, Jr. contributes to future science

WaTae Mickey, Jr. '26 is collaborating with Professor James Head to develop a reference mission for prolonged lunar exploration, a crucial step toward advancing extended space stays and future Mars missions.

WaTae Mickey, Jr. '26 is collaborating with Professor James Head to develop a reference mission for prolonged lunar exploration, a crucial step toward advancing extended space stays and future Mars missions.

As we stand on the brink of a new era in space exploration, the journey of designing missions to the moon unfolds with both complexity and wonder. For Brown's rising junior, WaTae Mickey, Jr., this journey is deeply personal and rooted in experiences and inspirations.

Growing up, WaTae Mickey moved between the frigid winters of Minnesota and the sun-soaked days of Arizona, and amid these geographical transitions, he found a grounding presence in his family—a vibrant, intergenerational household teeming with aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents. “Having such a large family meant there was always someone around to teach me something new,” he says. “It wasn’t just about learning from my parents, but also from my grandparents and extended family. They instilled in me a strong work ethic and a love for exploring new ideas.”

This sense of discovery and curiosity, fostered from a young age, now fuels his research in Providence, Rhode Island. The UTRA recipient is engaged in designing reference missions for extended lunar exploration, a task that connects his childhood wonder with his current academic pursuits.

In this Q&A, the future geologist explores his personal journey from childhood curiosity to lunar research, sharing insights into his inspirations, the challenges he faces, and the impact of his contributions to the future of space exploration with his research, The NASA Artemis Program Human Exploration of the Moon and Mars: Designing a 500-day Mars-Like Lunar Mission.

WaTae Mickey, Jr. '26

Q. What are you doing this summer?

A. I've been doing research with UTRA and right now I’m working with Professor James Head planning and designing a reference mission for a prolonged lunar exploration. My personal part in all this during the summer would be studying the origin of the Hadley Rille. What's the Hadley Rille you ask? Well, sinuous rilles are unusually long, river-like channels on the lunar surface, but unlike rivers, there's no water—especially near the Apollo 15 landing site.

These channels are agreed to have been formed via volcanic processes, but unfortunately scientists can't agree on exactly how. We are now employing a combination of photos, UV data, and machine learning techniques to enhance our rock identification process. This updated method aims to pinpoint areas with the highest probability of containing the desired rocks, despite the challenging environmental conditions on Earth and the Moon. The motivation behind this shift is the limited resolution of lunar images, which is approximately 2 feet by 2 feet per pixel—much larger than the rocks we are targeting. And well, it's been tough.

Q. Who inspires you to do this research?

A. That goes back to why I'm even a geologist in the first place. When I was little in Minnesota, my folks had a sandbox in the backyard, a huge backyard. And that's where I spent the majority of my time playing in the dirt and sand. Then my mom brought home a book about dinosaurs, and after going through it, I realized: "Oh, the paleontologists exist. There's a job out there where I can dig the dirt, search for dinosaur bones and get paid for it." After that, I was hooked—"I'm being a paleontologist no matter what!"—Well, now I'm a planetary geologist, so things have changed clearly, but one thing that has not changed is my love for geology and that's what inspires me to be here today. I love the field so much and I'm really thankful for my mother and my father for having a sandbox in my backyard, which got me hooked in the first place.

Q. Can you tell us why your research is important for you, for Brown, for the world?

A. I should say I got very, very lucky and blessed. My advisor [James Head], I mean what a guy! He helped out with the Apollo Mission, which means he is connected with pretty much everyone who worked on that mission, including the astronauts. Consequently, I get to meet people I never would've thought I could meet—astronauts and the NASA scientists. I mean, he is the planetary scientist and his whole goal is to train up a new generation of planetary scientists, and I'm one of them.

My goal is to head one of the missions to either the moon or Mars. I would love to be at the center of one of those, and in order to do that, I need the skill set for it. He is by far one of the best people to obtain that skill set from.

As for Brown, I mean, I feel like being connected to me after I succeed is a pretty good deal—I'm just saying. For free? Come on now [laughing].

As for the world as a whole, the work right now is a design reference mission. If you've ever heard of the Artemis mission—it's the next mission to the lunar surface that's going to have people on it. So we're working on a design revolution for 500 days. Artemis is not planning on staying that long, but Artemis is the first step in the prolonged lunar stay, it's basically the first step towards staying on Mars.

Q. What advice would you give to fellow Brown students aspiring to pursue a research field?

A. Look for research outside your field. Why? Oh, let's say I'm doing CS [Computer Science]. Well, have you considered that CS has applications in literally every field? So don't just look in one field and be like: "Oh, that's full. I can't get into it." In my geology group, we have a wide range of expertise. There’s an engineering PhD student, a computer science graduate, an architect, a visual designer, and even someone skilled in Blender [a free and open-source 3D computer graphics software tool]. We also have a chemist on the team. A project of this scale requires so many different roles, and only a small portion of them can be handled by geologists.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

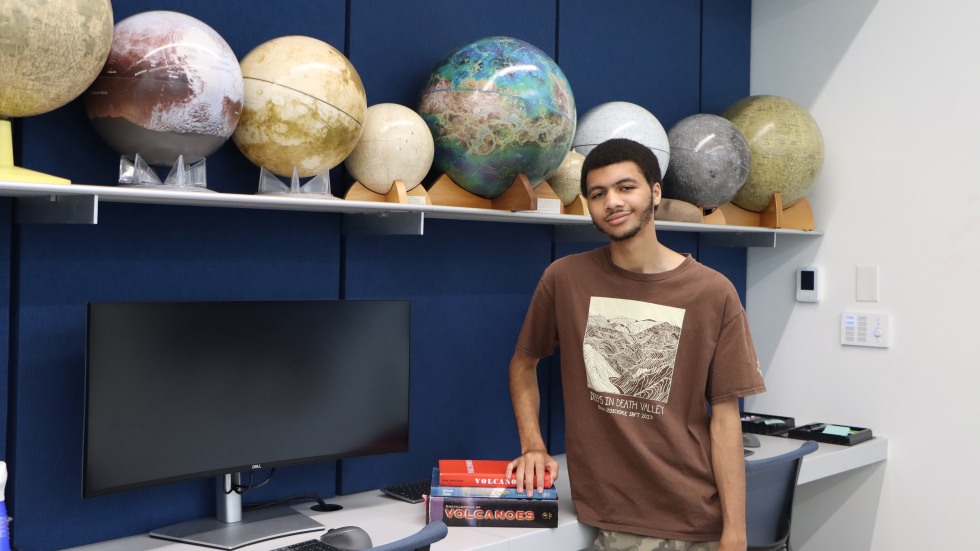

WaTae Mickey, Jr. '26 poses for a photo in the lab.

WaTae Mickey, Jr. '26 works in the lab.

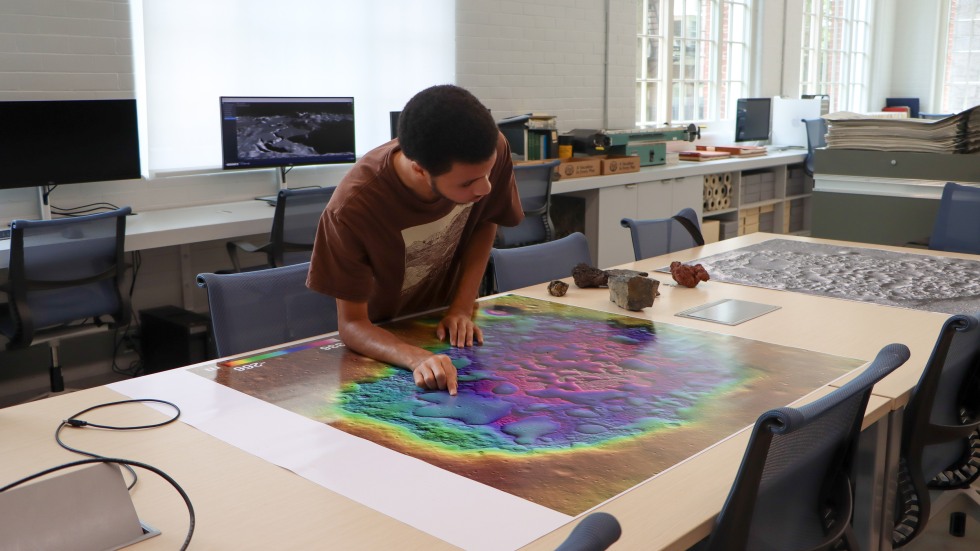

WaTae Mickey, Jr. '26 studies a map in the lab.