Revisiting the Story of Mesoamerica

Were the ancient Maya an agricultural cautionary tale? Maybe not, new study suggests.

Were the ancient Maya an agricultural cautionary tale? Maybe not, new study suggests.

For years, experts in climate science and ecology have held up the agricultural practices of the ancient Maya as prime examples of what not to do.

“There’s a narrative that depicts the Maya as people who engaged in unchecked agricultural development,” said Andrew Scherer, an associate professor of anthropology at Brown University. “The narrative is that the population grew too large, the agriculture scaled up, and then everything fell apart.”

But a new study, published in the journal Remote Sensing and co-authored by Scherer, suggests that that narrative doesn’t tell the full story.

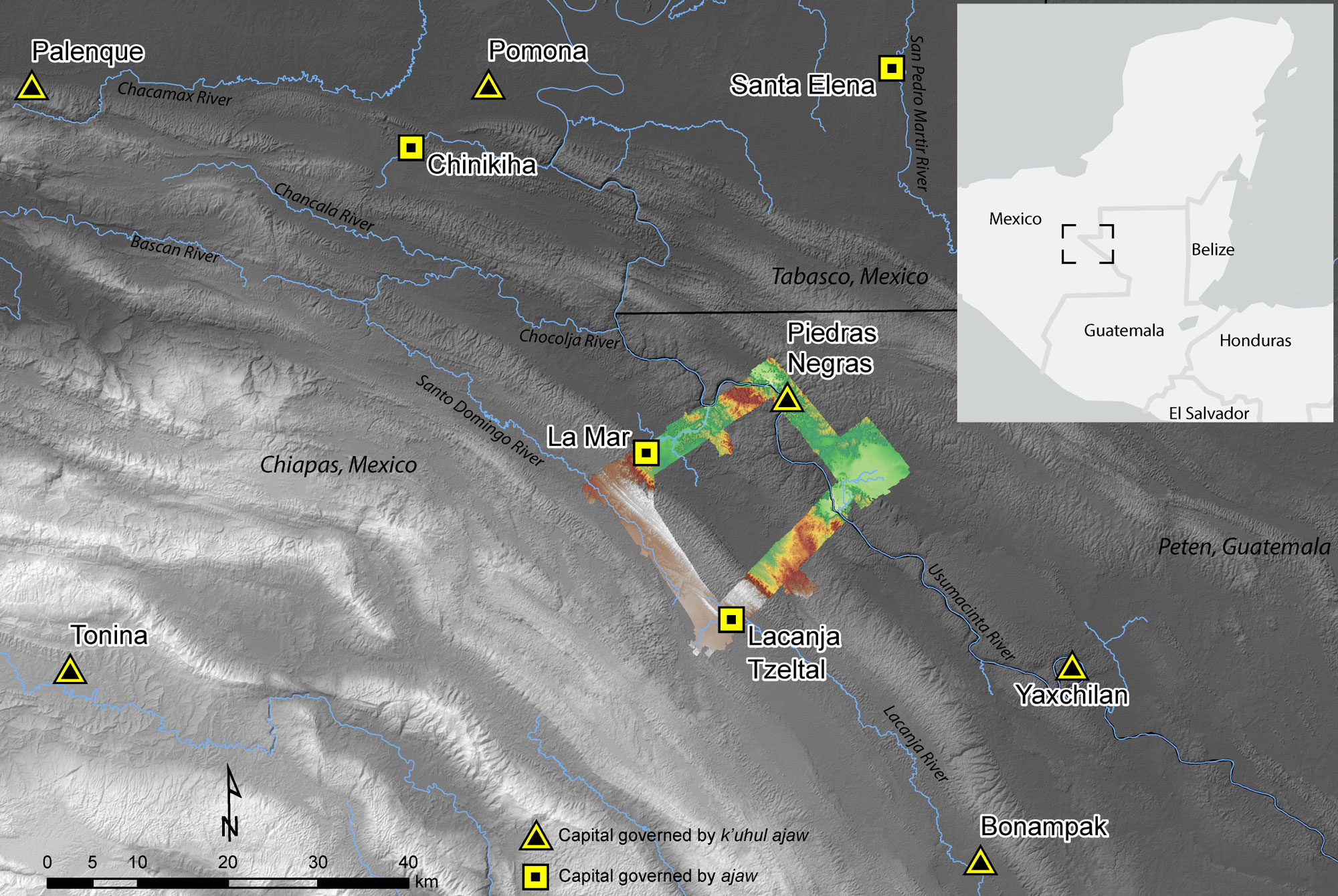

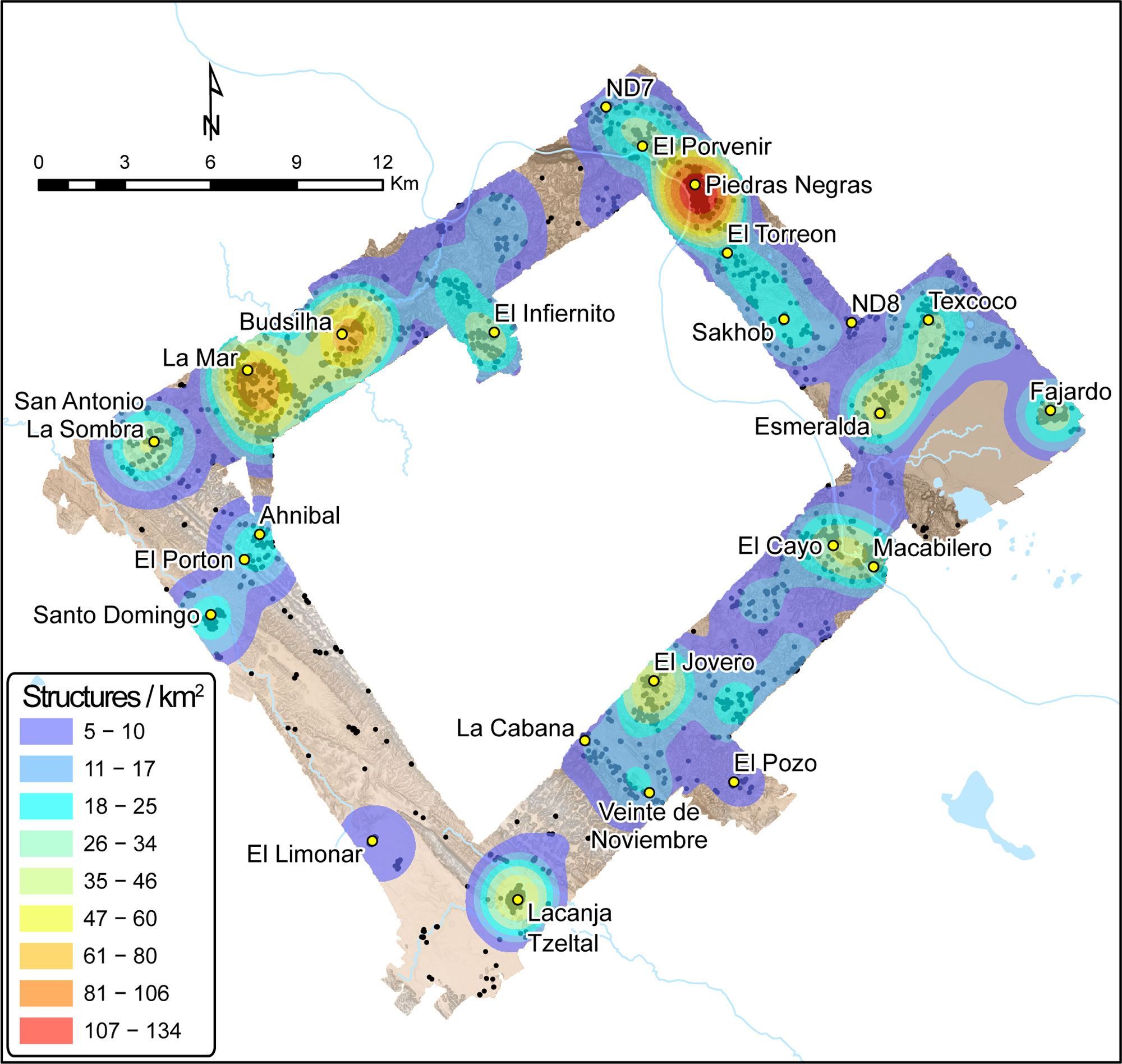

Using drones and lidar, a remote sensing technology, a team led by Scherer and Charles Golden of Brandeis University surveyed a small area in the Western Maya Lowlands situated at today’s border between Mexico and Guatemala. They focused on a rectangle of land connecting three Maya kingdoms that existed between AD 350 and 900: Piedras Negras, La Mar, and Sak Tz’i’. Despite being roughly 15 miles away from one another as the crow flies, these three urban centers had very different population sizes and governance structures, Scherer said.

“ Just as we celebrate the great feats of Rome or Greece, we should also acknowledge the many great accomplishments of the Maya and other indigenous peoples of the Americas ”

Scherer’s lidar survey—and, later, boots-on-the-ground surveying—revealed extensive systems of sophisticated irrigation and terracing, but no huge population booms to match. The findings indicate that despite their differences, these three ancient kingdoms boasted one major similarity: agriculture that yielded a food surplus, allowing citizens to live comfortable lives free of food insecurity.

“In conversations about contemporary climate or ecological crises, the Maya are often brought up as a cautionary tale: ‘they screwed up; we don’t want to repeat their mistakes,’” Scherer said. “But maybe the Maya were more forward-thinking than we give them credit for. Our survey shows there’s a good argument to be made that their agricultural practices were very much sustainable.”

The research builds on decades of work by Scherer to uncover new insights on how the Maya lived, interacted with the land, and communicated with other peoples in the region. In 2018, Scherer and colleagues from Brown and Brandeis University worked with residents in rural Mexico to uncover remains of the long-lost capital of Sak Tz’i’—“white dog” in Mayan—in a cattle rancher’s backyard. Scholars had been searching for physical evidence of Sak Tz’i’ since 1994, when they first identified references to it in inscriptions found at other Maya excavation sites.

Following their discovery, the research- ers shared initial findings in the Journal of Field Archeology. The research has since been widely covered in the international press, including a 2022 feature article in the New York Times and a TV program for National Geographic that will air on the Disney Channel.

Scherer said he hopes his team’s research helps shine a spotlight on a civilization whose society was just as sophisticated and influential as the ancient societies of the Mediterranean.

“Just as we celebrate the great feats of Rome or Greece, we should also acknowledge the many great accomplishments of the Maya and other indigenous peoples of the Americas,” he said.